In an age of corporate hacks and insider attacks, data sanitization—the process of securely and comprehensively removing data from IT hardware—is more important than ever. Following a data breach of any form, a company’s reputation can hang in the balance.

Here’s our guide to the critical role that data sanitization plays in preserving information security across the increasingly complex landscape that is enterprise computing, focusing on the data center.

- Playing Corporate Cat and Mouse

- Developing a Data Governance Framework

- A Process for Data Sanitization

- Pulling Drives

- Detecting HDD Failure

- Refresh Cycles and Data Sanitization

- The Case for Internal Reuse

- Sanitizing Hard Drives

- Approaches to Data Wiping

- Considerations Around Data Encryption

- The NIST 800-88 Standard

- The ADISA Standard

- The Business Case for Reuse

- Rules Of Thumb

Playing Corporate Cat and Mouse

Given the sensitivity of data and the increasing value companies derive from it, securing data is an issue that’s rapidly moved up the corporate ladder in most organizations nowadays, from the IT function all the way to the C-suite.

Keeping data digitally secure is a huge challenge for the enterprise, particularly with the sharp uptick in work-from-home arrangements as companies adjust to the realities of COVID-19. As hackers’ digital tools get more sophisticated, IT’s digital countermeasures seek to rise to the task.

Compounding these challenges, companies must also take into consideration the physical security of their data.

Whether in a cloud data center, on-premise, in remote locations, or anywhere in-between, data is contained on a variety of hardware, from flash storage to spinning hard drives through tape and optical media. It can persist in memory and is increasingly entwined with the fabric of the data center itself.

Meanwhile, organizations must account for their employees’ devices, such as laptops, smartphones and other mobile devices. IT asset management is a head-spinning proposition at the best of times.

Developing a Data Governance Framework

Any effective approach to information security must place data sanitization at its heart. But, in order to sanitize media, an IT team needs a granular understanding of where the company’s data lives: its data topography.

This is where an organization’s data governance framework, its overarching approach to data management, helps. In developing their approach to data governance, companies identify what kind of data they routinely generate and how to organize and store this information, dependent on business need.

Within the data governance framework should be guidance on data retention—how long to hold on to certain kinds of information and when to delete. As a rule, the longer a company holds on to data, the greater the risk of that data becoming subject to discovery in the event of a legal action or a security breach.

The principle of defensible disposition advises organizations only to hold on to data for as long as commercially necessary or legally required, although the reality is that companies tend to retain data whether they mean to or not.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve worked with organizations that have been the victims of a critical security incident or a data breach where the compromised system contained two or three times the data, sometimes even more, than for which there was any legal retention requirement or practical business need.”

-Attorney Peter Sloan of Information Governance Group

A Process for Data Sanitization

Setting the rules within the data governance framework is one thing: maintaining and enforcing them is another. This is where process kicks in—process based on a governance framework that is widely understood across an organization and centrally owned.

Because when it comes to data sanitization, the existence of clear policies and processes is key to preserving information security.

Even with the increasing adoption of AI-driven solutions able to automate the administration of policies, the management of storage media for data sanitization purposes requires human oversight: exactly which drives to wipe and how to handle the physical asset once out of deployment.

Pulling Drives

Deciding when to pull storage media from active use depends on several variables. Drive failure is a primary factor: each drive comes with an average life expectancy—the mean time between failures—calculated on the actual performance of that model drive in deployment.

The respective lifetimes of different model drives can vary significantly—it’s difficult to predict at the outset which model drives (and from which manufacturers) will prove to be the hardiest workhorses.

The best guide is actual performance in deployment, and for that we have good data. Every quarter, data storage leader Backblaze provides excellent analysis of the performance of the approximately 160,000 hard drives from the three HDD manufacturers—Seagate, Western Digital, and Toshiba—that it has operational in its data centers.

Detecting HDD Failure

A number of factors, often mechanical, can contribute to hard drive failures: the trusty HDD, since its earliest incarnation in the 1950s, has contained its fair share of moving parts. Even the smallest shock to the hard drive can result in a range of annoying, sometimes fatal errors— those platters spin fast.

Recognizing a hard drive issue is generally straightforward for a disk deployed on its own. For server-grade HDDs in random arrays of independent disks (RAIDs), however, the RAID controller is configured to isolate hard drive failures within the storage array. The RAID level deployed and the extent of the hardware failure will determine how recoverable—and rebuildable—the data is, or not as the case may be.

Once a faulty hard drive is pulled, technicians will identify the fault and determine whether the disk is capable of repair. At that point, decisions around internal reuse or external remarketing can be taken according to pre-set criteria.

In either scenario (and even if the drive is destined for destruction) , technicians will wish to sanitize the drive’s data.

Refresh Cycles and Data Sanitization

It’s not only drive failures determining which storage media get pulled: refresh cycles play a role, as data center managers seek to expand storage by introducing higher capacity drives into the available rackspace.

The calculus over when to run a refresh cycle is complex: while hardware refreshes support IT modernization, they carry a direct cost that leads many enterprises to delay. According to a Dell EMC survey conducted by Forrester Research, companies often prefer to avoid short-term expenditures even if it costs them operationally in the longer term.

“On average, 40% of server hardware deployed at company data centers is more than three years old,” the Forrester authors state. “Companies are adding capacity to support emerging workloads, but they retain aging hardware for four years on average, which is longer than ideal.”

It’s true that companies don’t always have the appetite for regular hardware refreshes. At the same time, it’s hardly the case that companies aren’t investing in new equipment. A 2019 survey from Spiceworks revealed that more than a third of organizations intended to invest in new server hardware in the ensuing 12 months, although the shock of COVID-19 will likely push firms to do more with what they already have for the foreseeable future.

In any event, there is always some level of storage media that needs pulling and replacing, and the accompanying question of what to do with the retired drives once sanitized, from redeploying the equipment within the same organization to reselling within the secondary market.

The Case for Internal Reuse

Although often overlooked, internal reuse of HDDs is a win-win for most organizations.

Financially, companies stand to benefit by reducing capital requirements for new media. From a performance perspective, older drives may no longer meet the needs of increasingly sophisticated workloads—but they will work perfectly fine for less demanding functions.

There’s also the environmental dividend: reusing rather than disposing and destroying keeps the device’s carbon footprint low.

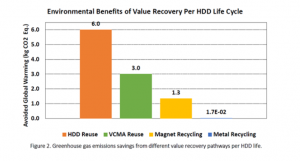

According to research from industry consortia the International Electronics Manufacturing Initiative (iNEMI), the carbon savings associated with the reuse of hard disk drives are significant—iNEMI highlights the positive global impacts derived from a variety of recycling use cases for HDD, with reuse clearly topping the list.

In addition to the environmental and financial upsides, there are operational benefits of internal redeployment. For example, when redeploying HDD internally, the requirements for data sanitization adopted by organizations are generally lower. Of course, it remains important to comprehensively wipe the media of its data, but the outbound checks that a drive earmarked for external remarketing are subject to can often be relaxed.

Nonetheless, it is important to have a clear protocol for the way redeployed drives transition within the organization:

- Are they staying within the same physical location or will they travel between sites?

- What is the process within the asset management database for tracking the device’s redeployment?

Whatever the protocol, the actions must be clearly documented and shared across the organization’s stakeholders.

“The enterprise should regularly validate the internal needs of the company for hard drive reuse. Back room or non-customer facing functions may be able to reuse the hard drive and defer the purchase of new drives by several years.”

-iNEMI working group on HDD reuse

Sanitizing Hard Drives

In spite of the many storage options and the growing dominance of flash for high availability, hard drives remain a dominant platform for data storage, whether on-premise, in colocation, or in the public cloud.

When responsible companies decide to upgrade and replace, or dispose of, outdated equipment, one of the considerations must be precisely how to wipe the data from those devices, or otherwise sanitize the hard drives where the data resides.

There are a number of approaches that can be used to delete data from hard drives, including deleting unwanted files; using software tools; encrypting the drives; or physically destroying the drive, by degaussing it (such that the drive is demagnetized by use of a strong magnetic field), drilling through it, or shredding it, to make it inoperable.

Too often data center operators opt to destroy without fully exploring the feasibility of reusing the drive in some fashion. According to iNEMI, many fully functioning HDDs are destroyed unnecessarily due to data security concerns. Amid fears that data might be left on the media after sanitization, hard drives are rendered inoperable instead of being reused or remarketed.

“This significant loss of potential value is caused by a lack of understanding and knowledge of the full capabilities of modern data sanitization methods,” the industry group states.

Approaches to Data Wiping

#1 Internal reuse

Not all wiping is the same. Simply deleting unwanted files or running a secure erase process might be all you need to free up storage capacity on a device that isn’t earmarked for redeployment.

However, if your intention is to redeploy the device internally, a more rigorous approach to data wiping is advisable.

Depending on the sensitivity of the data on the device and the nature of its new deployment—perhaps a different organizational function and a different data center—additional steps might make sense after wiping, such as:

- Validating the effectiveness of the wiping

- Issuing certificates of data destruction

- Erasing the device encryption key (assuming the drive is already self-encrypted) prior to transit

The exact approach you take will highly depend on the sensitivity of the data, your company’s approach to data management, its tolerance for risk, and any compliance requirements you may be subject to.

Build these guidelines around redeployment into your company’s data sanitization policy, and get your CIO’s sign-off. Proactively communicate and train around your policy, while building a culture that places a premium on information security.

#2 Remarketing and disposal

If the goal is to remarket or otherwise dispose of the drive, strengthen your process further and make sure workflows are rigorously documented.

There must be no room for procedural ambiguity when it comes to sanitizing data held on storage drives (and other data-bearing media) destined for resale or recycling.

Tight protocols around the validation and certification of data destruction are essential. These processes should be closely supervised by your company together with your IT asset disposition partner, with regular and predictable channels of communication around project visibility and reporting.

In addition to process implementation, practical considerations to address when developing your strategy for IT asset disposition (ITAD) include:

- Are the data wiping tools you or your vendor use industry certified? In what circumstances do you deploy OEM tools proprietary to the hardware or do you solely rely on commercially available software?

- When overwriting, how many passes do you stipulate relative to the data’s classification and what pattern do you require?

- From full drive scans to spinning down HDD for noise issues, what’s your process for ensuring maintenance and troubleshooting faulty media?

These are conversations to have with your asset disposition partner when developing your ITAD strategy, and thereafter around implementation on a project-by-project basis.

#3 A Note on SSD

While industry analysts anticipate HDD’s continuation as the dominant storage media in the enterprise data center, solid state drives are fast rising in prominence—supported by the growing adoption (and general favorability toward) the NVMe protocol.

At a technical level, SSDs require a materially different approach to data erasure than HDD. For example, to preserve the longevity of the device when overwriting data, SSDs are programmed (through the technique known as wear leveling) to write to a new section of the media rather than actually overwrite the existing data. The SSD’s flash translation layer then updates the block’s location to associate the overwritten data with its original address.

Facts like these initially led to serious concerns over the efficacy of data sanitization techniques for SSD, such as those raised in a 2011 paper from the University of California–San Diego. In the years since the paper’s publication, SSD wiping software has advanced significantly and is now more than capable of systematically erasing a device—provided the right software is used and implemented effectively.

Considerations Around Data Encryption

Cryptographic erasure is an alternative method for securely removing access to data on retiring storage media. It requires wiping the encryption key to data on a encrypted drive. Without the key, it is no longer possible to access the data.

This method is faster than wiping the disk sectors, which can be a lengthy process depending on the number of drives and passes involved.

It is also, theoretically at least, more secure than overwriting. Without access to the key, there is no access to the data—whereas even with the most stringent wiping protocols, concerns persist that data may get overlooked or left in hidden areas of the drive (hence the importance of validation).

Nonetheless, keep in mind:

- Self-encryption needs to be activated on the drive at the point of its deployment. Have a section in your data sanitization policy that addresses protocol around drive encryption.

- Don’t discount the risk of bad actors sidestepping the security layer and accessing the data in its unencrypted form in other ways—not least by locating back-up copies of the encryption key that fail to get deleted in the erasure process. As recently as 2018, there were reports of self-encrypted SSDs that remained structurally vulnerable to attack.

- There’s always the possibility that, at some future point, super computers will develop the ability to crack today’s encryption algorithms with devastating speed.

Despite these caveats, cryptographic erasure is generally effective and may be a way of encouraging greater adoption of storage device reuse. Specific recommendations for deployment of the method depend on an organization’s own circumstances.

In any event, cryptographic erasure must be coupled with processes for validation and certification to meet the appropriate industry guidelines.

The NIST 800-88 Standard

To shift industry behavior toward greater consideration of reuse before electing for dismantling or destruction, data center operators must feel confident in the thoroughness of the data sanitization process for hard drives.

For some time, the “DoD standard”, officially known as DoD 5220.22-M, was widely touted as industry best practice. The problem is that the standard was never intended to be a standard, and—in its stipulation of three overwrite passes—represents too heavy-handed an approach for most data sanitization cases, requiring additional time and cost. If the initial overwrite is sufficiently rigorous and thoroughly tested, isn’t that enough?

Despite this, the DOD standard, which originated in 1995, continues to get referenced in ITAD marketing statements today.

By contrast, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) guidelines for computer media sanitization, known as NIST SP 800-88, are widely considered to be the actual go-to standard. NIST 800-88 provides rigorous and comprehensive guidance for companies and U.S. government entities to ensure they are following best practices for data destruction.

The NIST standard recommends that once organizations decide to embark on a sanitization project, clear steps are followed:

- Verification of personnel competencies—meaning that anyone doing the sanitizing is competent and trained on the equipment to be used.

- Verification of equipment—meaning that the equipment that’s being used is properly calibrated and that proper maintenance procedures are used on the equipment.

- Verification of results—ensuring that the data to be sanitized has actually been sanitized.

“Sanitization is a process to render access to target data (the data subject to the sanitization technique) on the media infeasible for a given level of recovery effort. The level of effort applied when attempting to retrieve data may range widely,“ the NIST 800-88 guidance explains.

The ADISA Standard

Another standard that actively supports organizations seeking to achieve best-in-class control around data sanitization is offered by the Asset Disposal & Information Security Alliance (ADISA). ADISA conducts audits of companies who wish to become a part of the alliance, and once it’s determined that the company is capable of meeting the organization’s criteria, the company is eligible to apply to be certified.

ADISA has a rigorous process for certification. Once certified, ADISA conducts regular audits of at least two per year. These may include unannounced operational audits of each company, involving forensic tests of a sample size of 10 pieces of media. Full audits are carried out at least every three years.

The Business Case for Reuse

Data needs are growing wildly, and HDD will have a central role to play in the storage mix for a long time to come. Much in the same way that tape is still in deployment, HDD will remain a permanent fixture as nearline demand and drive capacity grow.

As such, we need to bring every effort to bear on prolonging the use of each hard disk drive in circulation for as long as possible.

By extension, when a drive has physically failed and dismantling is necessary, we must ensure the smartest possible disposition of the asset. Storage leader Seagate, a member of iNEMI’s HDD working group, calls for the creation of “hard drives from hard drives.” Researchers are working to develop innovative ways of reusing and recycling otherwise failed HDD components into new hard disk drives.

Nonetheless, many retiring disks still have a functioning life ahead of them. Through rigorous and professionally managed data sanitization, organizations can recover value from storage hardware, both helping the environment and the bottom line.

Rules Of Thumb

To build a robust data sanitization framework, follow these steps:

- Maintain a data governance framework that specifies the kind of data your organization routinely generates. Give parameters for handling and retaining each category of data.

- Spell out clear protocols for data sanitization within your data governance policy. Define the extent of human oversight when it comes to enforcing the rules for data sanitization. Ultimately, software is only as good as the humans who oversee it.

- Incorporate your company’s approach to hardware refresh cycles (as well as hardware failure) into your planning for data sanitization.

- Develop a proactive policy for the internal reuse of storage drives. For drives destined for retirement, explore all options for secure remarketing. Destruction should always be the final resort.

- Don’t leave details to chance. The security of your data is too important. Be prescriptive in your company’s expectations around the process for data sanitization and the secure handling of storage media and other data-bearing hardware.

From asset recovery to secure disposal, get in touch with Horizon for expert support with every aspect of data sanitization.